A pragmatic dream:

At the turn of the twentieth century, America was dancing in the midst of the extreme abundance that the Industrial Revolution produced. With the working class deskilled and labor unions being crushed, there was an allure to communist ideology. What won out instead was the pragmatic approach that viewed humans as fallible and the world as complex. It asserted that the household should be experimented with and improved upon just like the light bulb. As a response to the intricate designs of the Victorian homes and the materialism from industrialization, the bungalow movement was born out of American progressive ideas. The desire for simplicity manifested itself in the explosive growth of the bungalow home.

The materialism that swept America off her feet was in part because there was both access and appetite. Industrialism led to the access. Cheap goods were being mass produced for the first time ever so it is no wonder the average person wanted them. Most Victorian homeowners had servants. This contributed to making the wife a consumer rather than a producer (Hollitz 116). However, the practicality of one person being able to clean a simple house resulted in a rapid decline of female servants (Hollitz 132). However, the data shows that women did not stop entering into the workforce to become full time in their “home laboratory” (Hollitz 115). Instead, women clerical workers shot up exponentially between 1880 and 1910 (Hollitz 133). This indicated the changing gender roles were there to stay. The idea of progressivism marched on and left a wake of new change behind it.

The Victorian era home was full of unnecessary designs that required intense upkeep and the social status standards that came with it was just as exhausting (Hollitz 124). It was a detriment to middle class bank accounts as well as the average woman who was expected to take care of everything (Hollitz 131). This rampant materialism in American culture was set in motion in the individual home. Culture has been made up and shaped by individuals, that is evident across history. For example, Martin Luther King Jr influenced a generation of civil rights activists in America. The popularity of the bungalow is no different, it must start somewhere.

Those who helped shift the stagnant Victorian tide were Theodore Roosevelt, Gustav Stickley, and Edward Bok. Stickley started The Craftsman magazine in 1901 to get the ball rolling (Hollitz 112). The simple Craftsman home was much more than just a simple home. The core attraction was simplicity, but it was connected with ideas of freedom and a better future (Hollitz 113). These were shaped by progressive ideas that were in the process of taking hold such as the domestic science of homemaking. The Industrial revolution had made its way into the home — from the floorplan to the kitchen chores, it was all about efficiency. Edward Bok, who was a key player in getting the Craftsman movement off the ground, thought it was the answer to the “woman question” because the new bungalow would give women their own sphere of influence and involve them more at the household (Hollitz 110). Roosevelt similarly believed that the bungalow movement would cultivate more independent men with hardier virtues that he wrote about in “The Strenuous Life” (Hollitz 110). The pull that the bungalow home had on the American middle class was truly magnetic and its influence went far deeper than the foundation of the physical home.

The bungalow itself did not just appear one day across America but was slowly shaped and carefully designed to meet certain needs that the market demanded. The working class needed a way out of clutter and a way into home ownership. The bungalow just happened to be the vehicle that significant change would be accomplished by. Stickley knew that standards of living were influenced by domestic life (Hollitz 124). The sentiment for simplicity would be accomplished by having simple floor plans that are easy to clean. Additionally, by filling the home with what is natural, in turn eliminating all unnecessary furnishings. The connection to the natural, while a subtler aspect, gave the movement a more broad vision. People were starting to understand the importance of connecting to nature. Roosevelt put in a large amount of national forests and parks. The outdoors were also being brought into the home as well. Furnishings made out of wood and stone were becoming popularized at the beginning of the twentieth century to replace the ornate things that softened men and entrapped women (Hollitz 122). Idealistic movies were creeping in on something as rudimentary as a fireplace. These things are not happening randomly and pointed to something bigger occurring that would lay the groundwork for the 21st century.

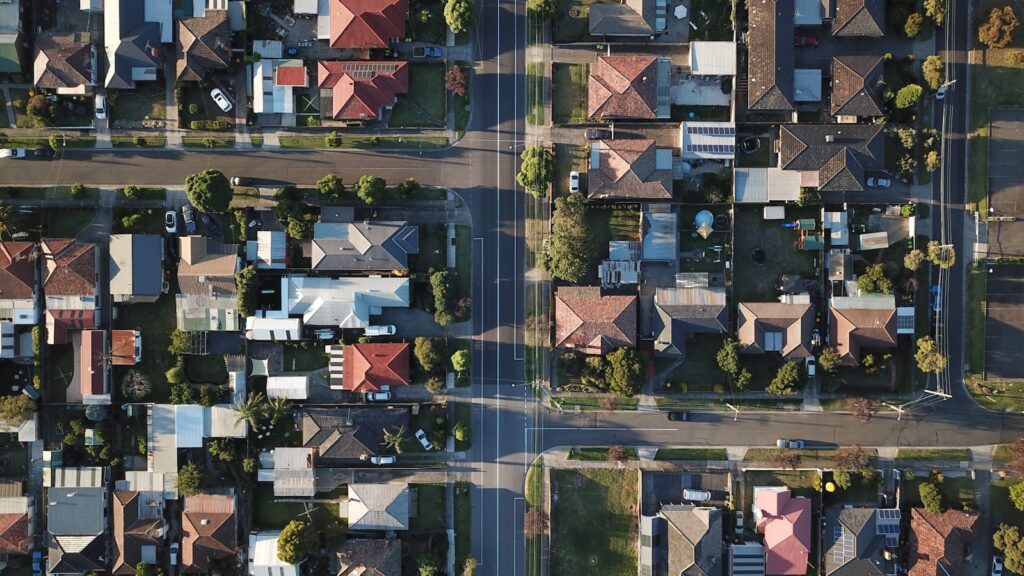

America still very much lives as an excessive first world country with problems of materialism, masculinity, and declining community involvement. The bungalow solution did not solve every issue the progressives claimed it would solve. However, its influence can be seen in the current middle class suburban sprawl, and it made it possible for women to work and take care of the house in a way that freed up both servants and housewives to pursue other opportunities. The bungalow was more than just a new type of house, it was a reflection of a culture of pragmatic middle-class Americans and their desires. The bungalow craze showed the power of ideas in action and the first half of the 1900’s would prove that too, only in a more violent fashion.

Correlate thesis statement to paragraphs

Past tense consistency are happening vs happened it was 100 years ago

No colloquial phrasing

Leave a Reply